Mark, Steve, Carra, Steve and Tim in more adventurous days.

This is the only picture ever taken where Carra was not in the back row.

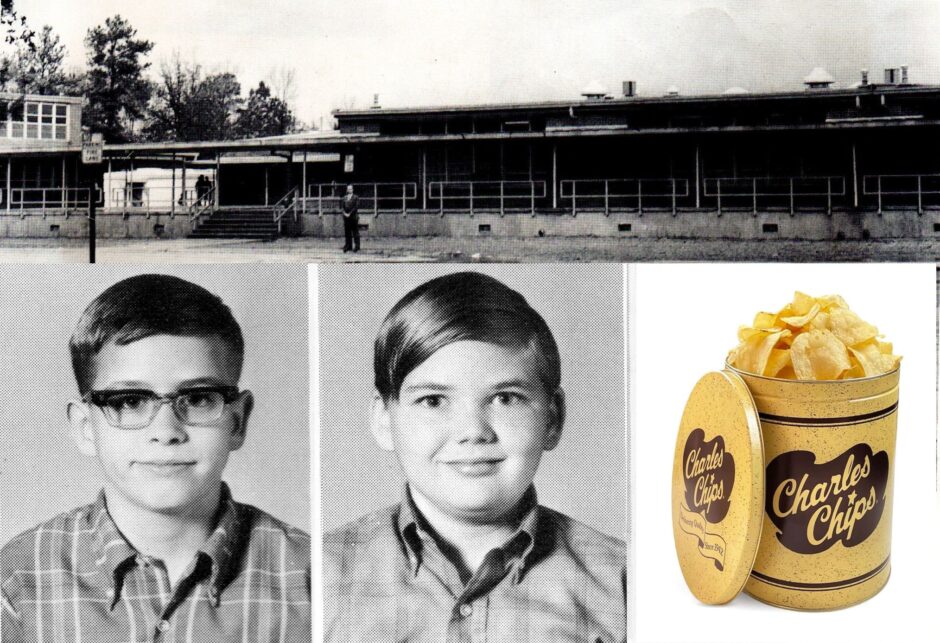

September, 1969. On the first day of sixth grade at Cloverdale Elementary, I was transplanted from my 5th grade cohort, which included my best buddy Mark Cook, into an entirely different classroom. There I met a really-tall-for-sixth-grade, soft-spoken fellow named Carra. Carra was the tallest boy in class. I was the shortest boy in the class. When standing side-by-side, we looked like different species. In spite of that, we quickly ended up great friends.

At recess, my new friend joined Mark and my older friends, and some things naturally changed. Carra did not run so much as lope, and playing tag with him was a whole different ballgame. When tagged, he would reach out and tag you back long after you thought you had safely escaped to a neighboring zip code. Rather than pure speed, the game became a test of agility involving twisting and ducking to avoid those long arms of his.

September 13, 1969. New friend Carra attended my 11th birthday party.

Scooby-Doo premiered that morning. A good day.

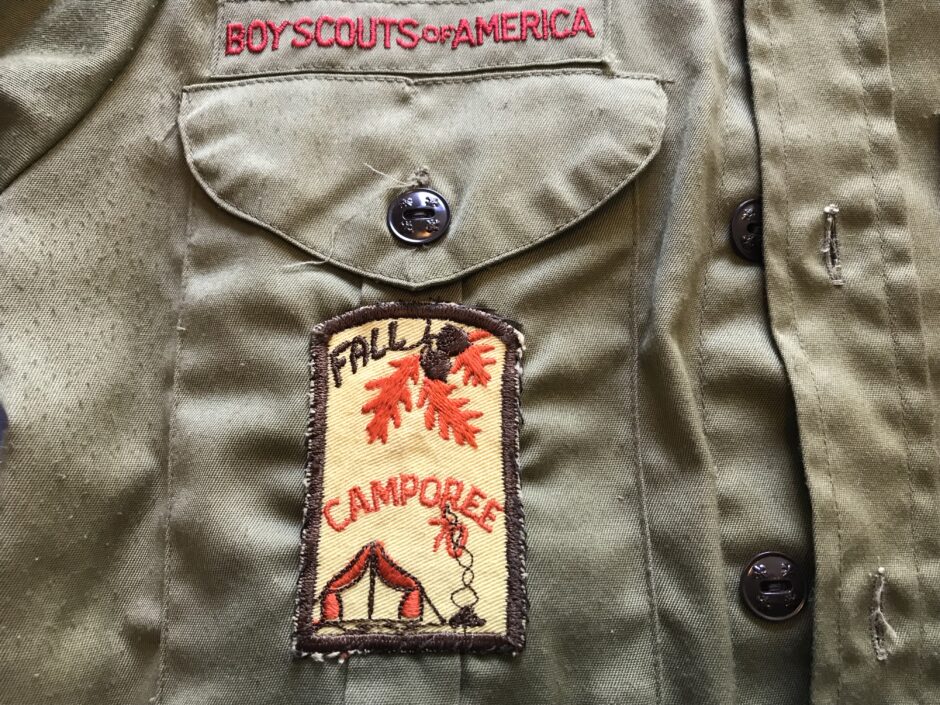

Carra and I were nerds back before being a nerd was cool. Carra and I shared a love of science and science fiction. With David Stebbins, we viewed moon rocks at the science center. Tim Teague, Mark, Carra and I had overnight chess parties where we, you guessed it, played chess, which goes to show that we were not your standard wild and crazy guys. We built and shot off model rockets. Tim, Mark Cook, Mark Griffin, Carra and I formed a “little German band” performing such scorching tunes as “Ach du Lieber Augustine” on 3 trombones, a tenor sax and a trumpet. Being a nerd obviously did not involve acting the least bit cool. Fortunately, we did not care that we were not cool, which is, oddly enough, what made us cool.

Mark Griffin later joined us on trombone, since the only thing better than 2 trombones

is 3 trombones!

Carra lived in a large house that would have suited the Addams Family. It was full of crazy things like electric vibraphones and ancient hand-cranked record players. Surrounded by large meadows and a lake, it was a great place to search out specimens for our 10th grade biology wildflower collections. The house had a deliciously creepy attic, always good for a thrill at one of the overnight chess parties. Once, while Carra and I were crouching behind a wall at 2:00 a.m. playing hide and seek, a family of skunks ambled by within spitting distance. Carra and I held our breath, stood as still as statues and escaped without being sprayed. We immediately resolved to remove hide and seek from all future overnight chess parties.

Playing chess. Carra was already planning his next snack attack.

By high school, Carra was 6 feet 6 and a half inches tall. A hundred times, I heard people ask him if he played basketball. He would good naturedly answer that no, he did not. He would also smile and act amused when a new acquaintance said, “Carra Bussa? What is your middle name, TRUCKA?” I heard that one so many times that *I* wanted to strangle some folks. His middle initial was M, so it obviously should have been Moped-a. Were they even trying?

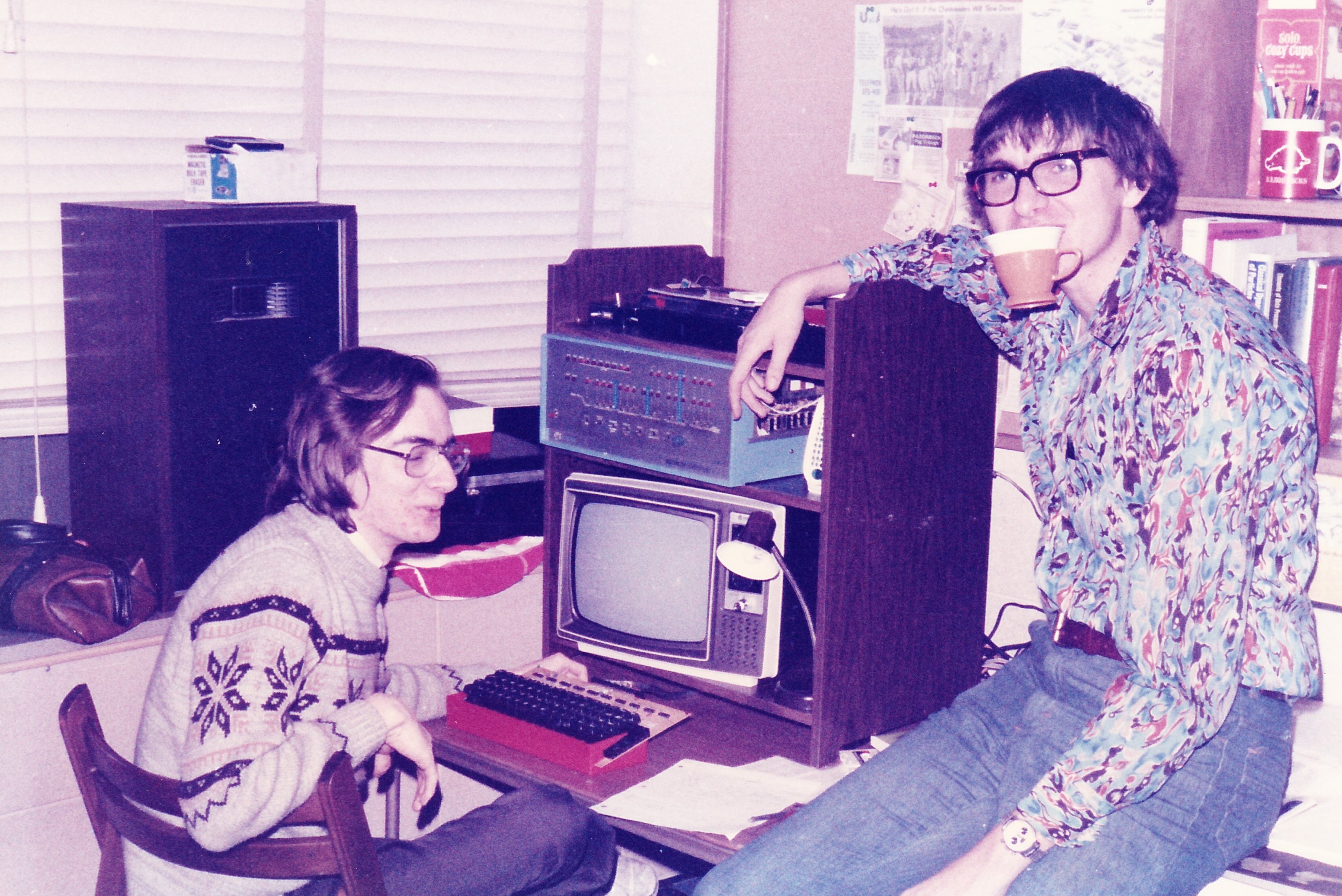

Carra, Steve and the two Marks computer gaming in the Stone Age.

Notice that we placed the Tostitos as far from Carra as possible.

Being so tall, Carra faced many challenges. He never encountered a mattress his feet would not hang off of, nor a ceiling fan that did not bop his noggin. In our McClellan band marching performances, when Carra marched away from the spectators, the green soles of his size 15 ½ shoes would flash hypnotically with every step. All the band members had to buy white-soled shoes because painting the soles left paint flakes all over the field like bread crumbs scattered by Hansel and Gretel.

Carra standing perilously close to a hanging light fixture.

He liked to live dangerously.

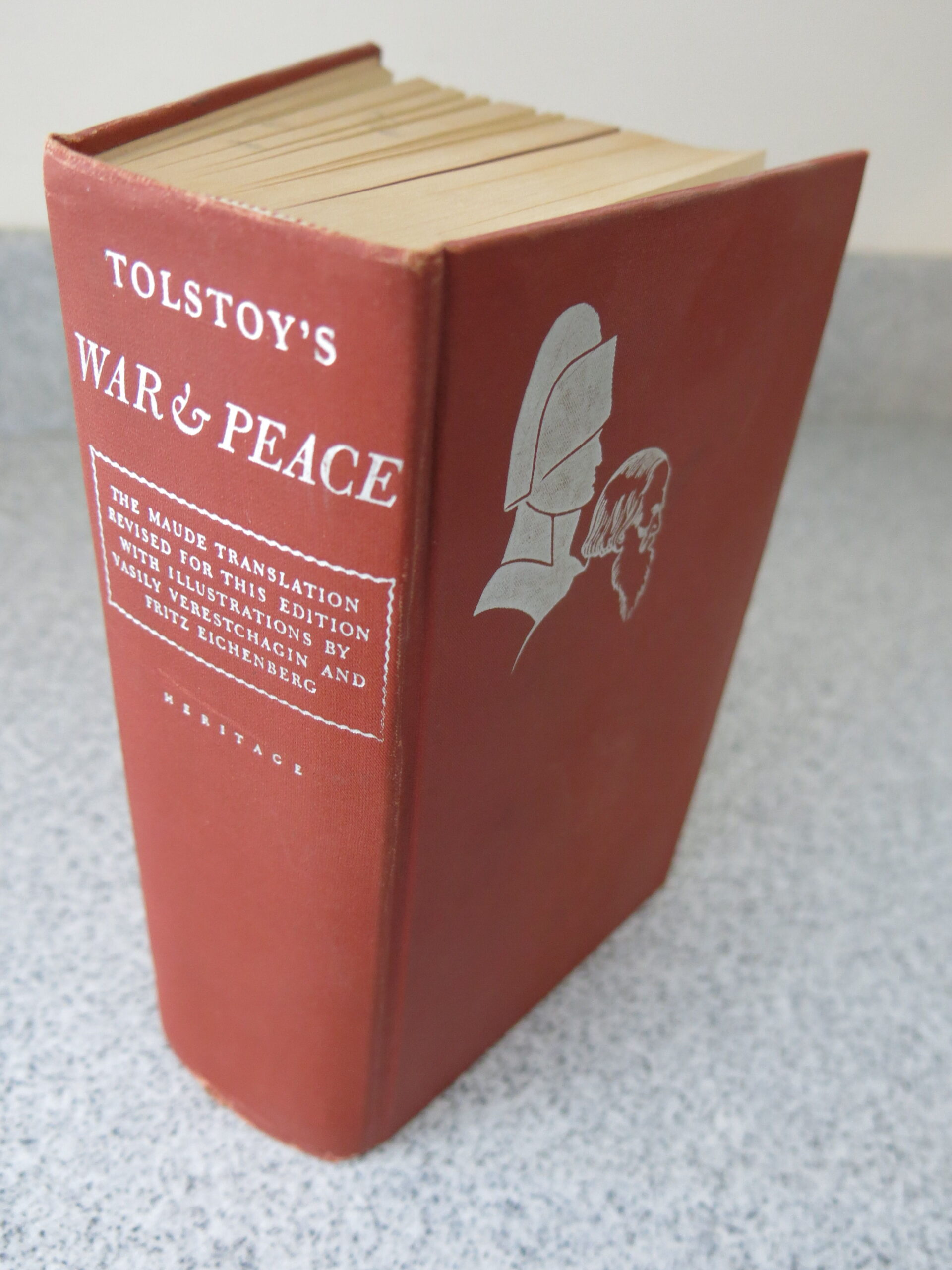

Carra could be annoying from time to time in spite of his good nature. When “War and Peace” was due in English class on Monday morning, I still had 500 pages left to read on Sunday. By pure serendipity, the movie was to be shown on TV that day. My English grade would be rescued! Upon my return from a hurried restroom visit during the final commercial break of the show, I was surprised to find Carra standing in front of my TV with his hand wrist-deep in a bag of Chips Ahoy cookies. He was watching the weather report even though it was obviously snowing just outside the enormous dorm room window over his shoulder. I flipped the channel around until I located the film, then sat to watch the final 15 minutes. Oddly, the movie did not end when expected, and furthermore, Napoleon was acting a little loopy. I had found a completely different movie about Napoleon! A comedy! I never did learn how “War and Peace” ended. To top things off, Carra never thanked me for not tossing him and his cookies out the window.

Carra with surgically attached solo cup for hands-free Coke consumption.

Once, after an evening of playing cards at Steve and Theresa Bour’s home, I was following Carra down Geyer Springs Road. A small flame began flickering under his car, right under Carra’s butt as if he had enjoyed too many beans at dinner. I honked and flashed my lights, and soon Carra turned down a side street and got out of the car. We watched as the flame spread, eventually to burn the entire car, popping the tires and causing the horn to sound a comically mournful death cry. Just when the fire was obviously not going to stop, Carra made a funny sound and ran back to the car. He flung open the car door and reached in, as heroic as a fireman saving a baby. Returning to my side, he bore the copy of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” that he had borrowed from me that evening. A friend will let you know when you have done something a bit unwise. A good friend will tell you when you have done something stupid. That evening, I was perhaps the best friend Carra ever had.

Carra’s vehicle, a 1967 Dodge Charger,

which we called the Batmobile.

Carra’s love of junk food, which included such goodies as the aforementioned Chips Ahoy, Coke, pizza, and pimento cheese on raisin bread, could sometimes get him into trouble. When Mark #1 (Cook), Tim, Steves #s 1 & 2 (Bour and Hendricks), and my brother Randy went on a canoeing weekend with Carra, Randy and I were rowing the canoe that carried a large bag of assorted goodies. Around mid-morning, I discovered a new treat hiding behind the buns – Au Gratin flavored Ruffles potato chips. I popped the bag open in order to sample them. The next couple of hours, I resampled the chips to verify that they were as good as my initial assessment indicated. When lunchtime came, I handed the bag of treats to Steve, who looked at the bag of chips and exclaimed heatedly, “CARRA! YOU ATE HALF THE CHIPS!” Carra pled his innocence, I admitted my culpability in the matter, and both Steves felt guilty for the rest of the day.

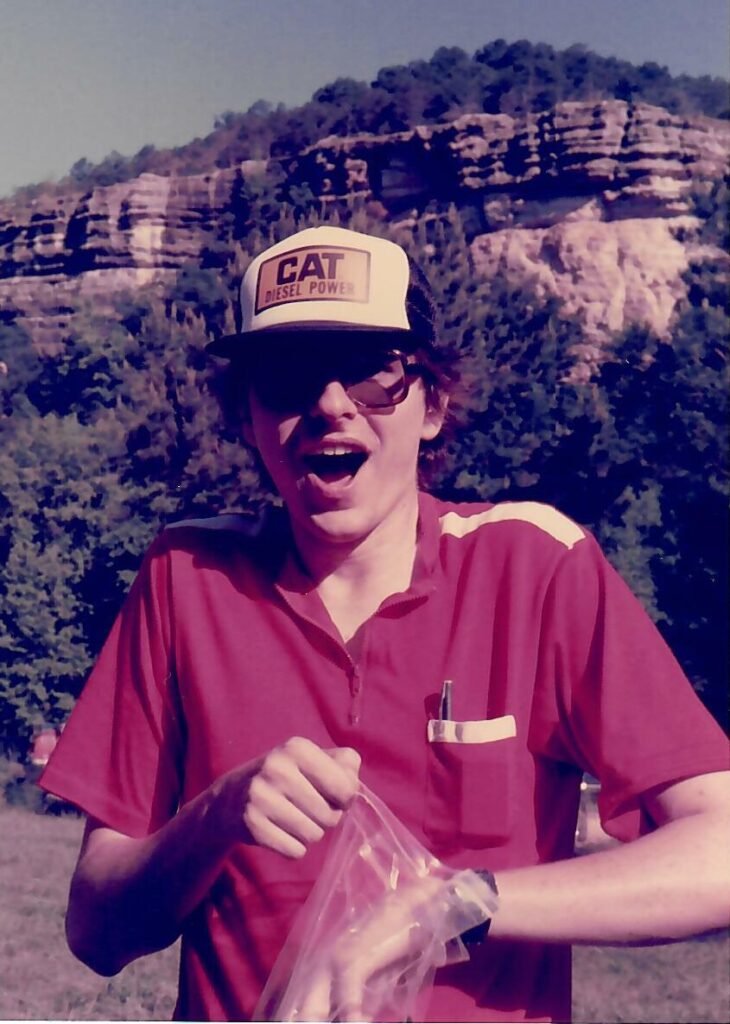

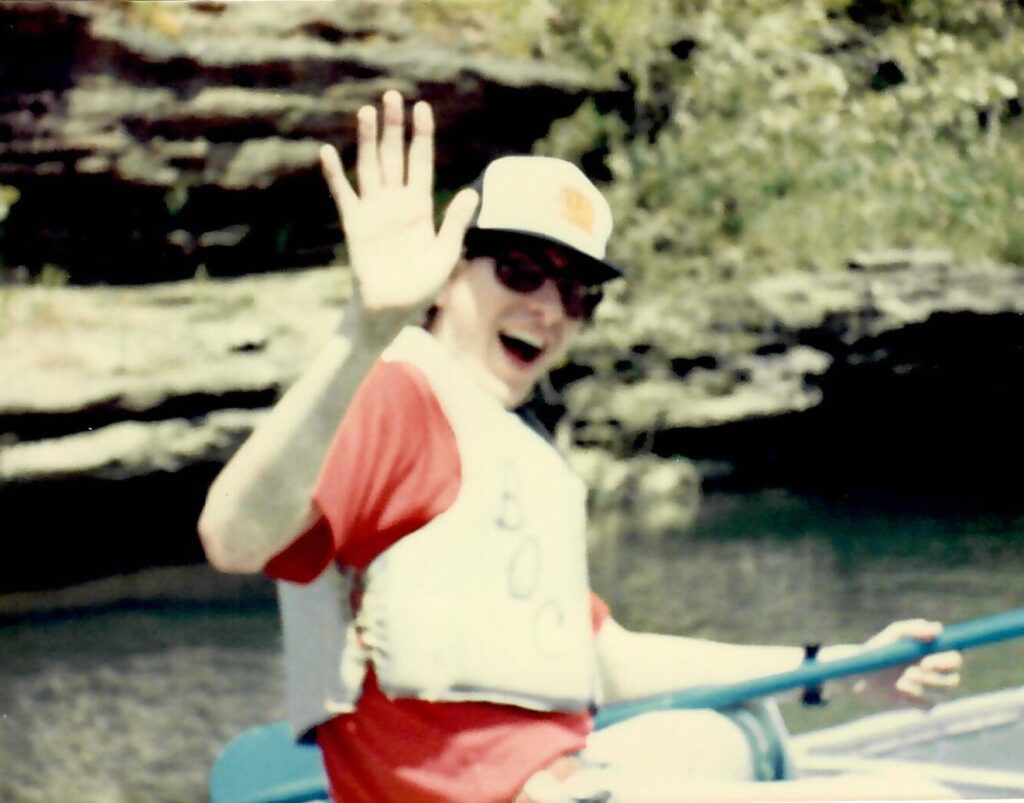

Carra indulging himself on the canoeing trip

prior to being accused unjustly of indulging himself.

It is hard to believe there will be no new adventures with Carra. No driving 120 in the Batmobile heading to Farrell’s in McCain Mall, no more halftime shows or crazy band bus rides, no overnight chess parties, no calculating whether a medium and a small pizza were a better deal than a single large, no road trips with walky-talkies to communicate.

I like to think that some part of Carra is still with us. With a science fiction paperback in one hand and a cornucopia of Coke, pizza and Chips Ahoy close by, Carra will continue to live in our hearts and memories, even if his feet will inevitably stick out the end.