My friends were depending on me to knot the rope and save us. Everything hinged on my dusty Boy Scout knot-lore, and things were looking as grim as an 8 am meeting in the principal’s office.

Years earlier, my parents decided I needed hobbies other than reading comics and watching Gilligan’s Island reruns. Options were limited in Arkansas circa 1968, so my new adventure entailed joining Cub Scouts and learning to make authentic Native American drums from Folger coffee cans.

Each week, Mom dropped me at the home of my Cub Scout Den Mother. This misguided woman must have loved spatter as a decoration motif, given she routinely hosted ten year old boys armed with paint, glitter, and squirtable bottles of Elmer’s glue.

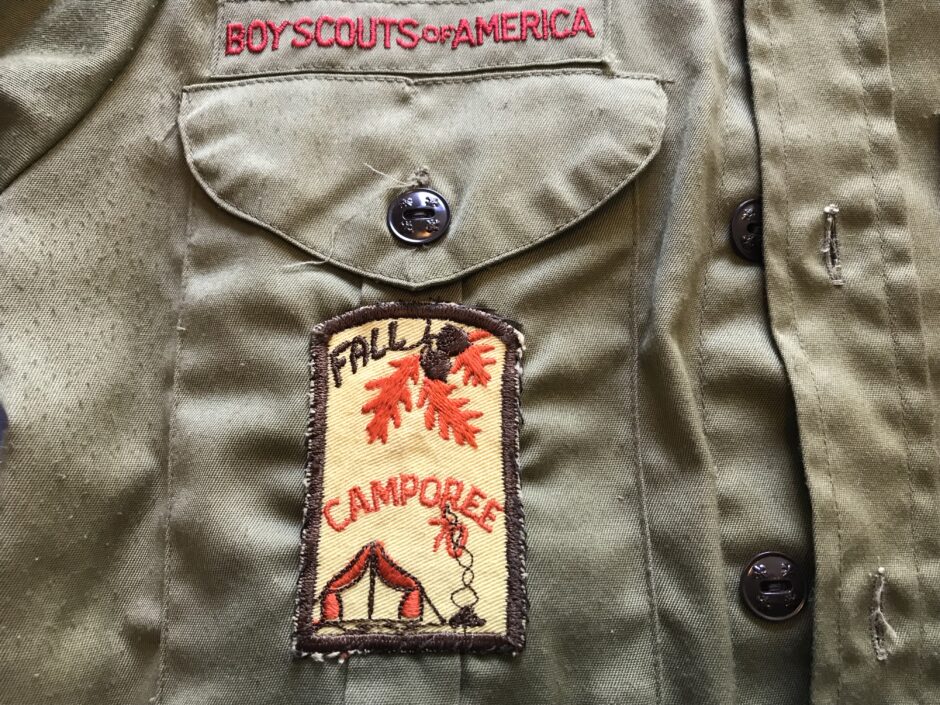

After years of defacing coffee cans and not a few items of furniture, I matriculated to the Boy Scouts of America, or BSA for short. Since I needed a new costume and accoutrements, Mom drove me to the Official Boy Scout Store. There you could purchase overpriced official scout gear in various shades of khaki, sort of like Louis Vuitton for tragically bland tweens.

We bought an official scout back pack, shirt and trousers, cap, scout manual, and neckerchief. We did not spring for the official scout pocket knife, compass, tent, sleeping bag, hiking boots, matches, flashlight, flint and steel fire starter kit, or the (conveniently never needed) snakebite kit. I urged a splurge, but Mom was reluctant to sell internal organs to pay for it, even though she was hardly using her spleen at the time.

The Boy Scouts organization was something of a paramilitary wannabe, with rank earned by acquisition of skills. Emphasis was placed on expertise deemed necessary upon debarking the Mayflower with only a pen knife, a prayer book, and a hat with a buckle on it.

Like all scouts, I started at the bottom of the pecking order. The entry level rank was called Tenderfoot, which in my case equated to “Dies when left without potato chips.”

After learning something tangentially useful to modern life, you could ascend to Second Class, then to First Class, and maybe another one or two until you got to Eagle Scout. At that point you were qualified to wrestle grizzly bears in your official Scout loin cloth.

In those days, to achieve Second Class, you had to endure three ten mile hikes. There were other feats and oaths involved, but those excursions were my particular bane. I had a disease in my knees known as Osgood Slaughterer’s Disease, so my knees hurt often, and the pain worsened with exercise. Long hikes settled on my list of preferred pastimes just under listening to Great Uncle Bill enumerate his prostate issues.

My scout troop Leader was a wiry little guy named Mr. Valez. He had a curious accent that always put me in mind of German war criminals escaped to Venezuela. He would clip his words, hammering consonants as if they were wanton gophers frolicking in his flower garden.

Mr. Valez plastered his graying wavy hair to his scalp with something resembling bacon grease, and was a stickler for the Boy Scout Way. He was not the kind of guy who would let you slide by with just two ten mile hikes. Like a mistranslated Nazi interrogator, he had ways of making you walk.

Early on, I had ticked off all the accomplishments needed to advance several levels except for that confounded third hike. Being a Tenderfoot for two years was very disheartening, and I found myself caring less and less about the scouting skills I had mastered. Before long, I had forgotten how to tie a half-hitch, build a dam from Popsicle sticks, and skin a ferret using only an old sock.

One weekend, there was a big camp-out on Sardis Road, a semi-rural bit of land being eyed for future housing development. The construction company had offered use of the land to the scouts in the hope we would chop down trees and wreak extensive havoc, thereby saving them some land clearing costs.

Mr. Valez informed us we were in for a treat for Friday night supper. We lit a fire, set up a tripod, and suspended a coffee can (without drum decorations) over the fire. We filled the can with water, potatoes and carrots and let it hang over the fire while the smoke blew straight in my eyes for what seemed like 7 hours. During the wait, we did all that scout stuff Mr. Valez lived for, like talk about scouting, play scout games, recite scout pledges, and pee in the woods.

When the stew was ready, Mr. Valez spooned some into our official Boy Scout mess kits. I detected subtle but unmistakable undertones of Maxwell House. Everyone but Mr. Valez gave the stew a pass because it was godawful to the last drop.

While the Boy Scout motto is “Be Prepared,” temperatures unexpectedly dropped that night, and we were caught with our cargo shorts down. I had not packed for weather less temperate than balmy to middling chilly. My light windbreaker was woefully insufficient. My black leather Buster Brown dress shoes were useless against the cold. In short, I was woefully undersupplied for an expeditionary force in the frigid heart of Southwest Little Rock.

That night, I discovered that my sleeping bag was little better than an oversized pillow case with a zipper. I crawled from the bag, assumed the khaki, and took a hike (figuratively only, alas). A few of my fellow scouts were standing around the fire trying to warm up. I had lost feeling in my extremities, so I held one foot over the fire hoping to stave off frostbite. My preferred toe allotment has always been ten.

After a couple of minutes pondering how smoke always knows where your eyes are, I was startled from my reverie when my friend Andy McGee pointed out that my shoe was smoldering. In fact, little flames were flickering off the shoe itself. I stomped out the fire, but the melted rubber underside caught up grass and leaves before it solidified again. Even with the avant-garde fashions of the early 1970s, I was the only kid sporting a shoe with dead flora embedded in the sole.

An hour or two before the sunrise, I slipped back into my sleeping bag. As daylight appeared, Mr. Valez creeped into the tent to awaken us. I was very groggy, so he grabbed me by the shoulders and shook me. My head snapped back and forth on my shoulders like a rubber chicken in an over-caffeinated Rottweiler’s jaws.

Eyes wide with horror, my tent mates Mark Cook and John Farr jumped from their sleeping bags, as awake as if they had simultaneously experienced a double espresso, a generous snort of cocaine, and an electric shock to the genitals.

I was still groggy and now dazed as well, but Mr. Valez decided to apply a little more stimulus. He snapped my head back and forth a few more times. Mark and John looked on, laughing nervously, while my noggin made those cartoon punching bag noises, buggeda, buggeda, buggeda, buggeda.

I begged him to stop while my head was still attached, so he left to torment other kids. My abused neck put me in mind of Marie Antoinette, but there was not even any cake for consolation.

Later in the day, it came time to show off our Scouting expertise in competition. In the center clearing, the older scouts demonstrated the most vital of all survival skills. Reverently passed down from generation to generation, we called it “cheating.”

Lessons learned that day include that a wristwatch will help you time a run better than counting, and that flint and steel are hopelessly outclassed by a Zippo lighter, especially one with a topless hula girl etched on the side.

At the knot tying competition, we lined up and were each presented a short length of rope. My best friend Mark and I were the last two in line. The judge came along and gave each of us a knot to tie, such as a bowline, clove hitch, or stopper knot. When he got to me, he pointed at the rope and declared, “inverted Möbius strip knot”, or some such thing. Of course, REAL scouts could tie this knot one-handed while extemporaneously composing an ode to small woodland mammals.

So there I was, stymied by a piece of limp hemp. I had forgotten every blessed knot except the common Granny knot and her straitlaced cousin, the square knot, neither of which the pitiless bastard had assigned to me.

Mark quickly and competently tied his knot. He shrugged sympathetically, knowing there was not a chance in hell that I could tie my knot or help me, best friends or not, with the scoutmaster just feet away. I distractedly tied a square knot as I watched the judge shuffle along the line toward me and Mark.

After awarding Mark ten points for correctly tying his assigned knot, the scoutmaster looked at the rope in my hands. “Square knot?” he asked.

“Yes,” I mumbled, eyes downcast with shame because I had been caught out, “it is a square knot.”

“Great! Ten points!” he said, turning and heading away to tally up the points. Mark and I turned to each other in shock and relief. I had gotten the points without deserving them! The elder scouts later expressed admiration for my innovative use of truth and sincerity to devise a whole new class of cheating. I was a bona fide hero, the living embodiment of the BS in BSA.

Soon after, scouting fell from my attention, replaced with Operation Hormone Storm and the attendant rediscovery of girls. Thus began my miserably shy dating period, when I found talking with girls difficult (fortunately this spell promptly ended when I turned 40). Even so, frustrated dating was preferable to tying knots, melting shoes, and eating coffee flavored stew.

However, I soon found that, in courting as in most endeavors, it is rare to win ten points for guileless ineptitude.